Utilising Learning Styles To Increase A Child’s Potential

This article is not about any particular panacea for developing potential in children. It is about understanding how ‘learning styles’ can help raise awareness in children as one in a number of processes of HOW they learn.

When I was young, my parents used to look at me with loving, caring eyes and say things like, “You know son, you’ve got potential!”. I think a teacher of mine said it too. You might identify with this statement in your own lives, or even heard yourself saying it to one of your children or pupils. To be honest, it was a label for me that I wasn’t really sure what to do with and in hindsight I probably should have asked back, “the potential to do what (and how do I do it)?”.

By definition ‘potential’ means having or showing the capacity to develop into something of value in the future. Take a lump of plasticine. We could say, “You know what, that’s got potential”. We could just leave it to see, if by accident, the external environment shapes it into something that has value. In truth it probably needs a bit of shaping and nurturing until it develops a shape that we can identify with. Then we can can start to realise its ‘potential’ of what it could become.

I believe that if you are, or become adept at shaping your own linguistic and nurturing abilities, then you too could further help shape a child’s potential (not that you don’t already). So what has ‘learning styles’ got to do with increasing a child’s potential, and how could learning styles influence that potential?

Learning styles, by definition, can often be described as an individual’s mode of gaining knowledge, via a preferred or best method. This can be further realised by one’s awareness of strengths, weaknesses and preferences.

There is substantial literature about different learning styles models which I will not go into here. If we apply an ‘NLP lens’ to learning styles we are concerning ourselves with ‘learning modalities’ via our senses (a model initially proposed by Walter Burke Barbe).

In NLP terms our senses are the ‘raw ingredients’ that make up our experiences. Seeing (V), Hearing (Auditory, A), Feeling (Kinaesthetic, K), Smell (Olfactory, O) and Taste (Gustatory, G). Other senses are known to exist but are outside the realms of this article. These senses are how we navigate our world. Our brain processes information coming in through our senses, into neurological signals within the body. In this article I am describing the utilisation of just 3 (V, A and K) as these are widely accepted as main senses.

Allow me to take you back to the time where you sang “2 plus 2 is 4, 4 plus 4 is 8, 8 plus 8 is 16, etc. A perfectly good auditory (A) strategy, as it involves learning and memorising through sound. This worked particularly well for myself when it came to ‘early years’ addition principles. I didn’t know this preference at the time though! If I had been taught, or developed a belief, that seeing (V) the numbers on a black board was the only way to learn, I may have done myself a long term disservice and lost confidence in my maths abilities.

Some younger children may prefer to use their fingers to group together, to see (V) and feel (K) , when comprehending addition and subtraction. Likewise, they might not know this, but they just know that it works for them. Kinaesthetic and visual ways of learning maths exist through products such as Numicon. This uses what I describe as large pieces of flat, coloured four sided structures (a bit like flat Lego) which gives the learner an appreciation of the size, pattern and feel of a number quantity, rather than seeing just a set of numbers on a board.

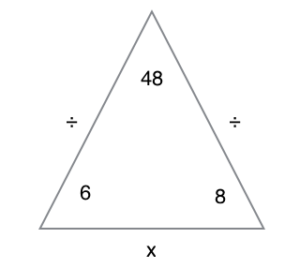

Here is something many of my clients (both younger and older) find useful when it comes to multiplication for example (see triangle diagram). Rather than ‘saying’ the times table, they often find it more memorable to see it as a pattern or structure in their minds. Multiply the bottom two numbers (either way) to get 48. Dividing the top number 48 by one of the other numbers at the base of the triangle, results in the remaining bottom number. It is important to have the result of the two multiplied numbers at the top of the triangle.

I challenge you now, to take a few moments and make a snap shot of this with your vision and then look away to recall it in your visual memory. Sometimes projecting your visual image of the triangle and its numbers onto a flat surface, like a wall, can help accomplish this.

For those that haven’t experienced doing this, it’s like the seeing the residual image of a light bulb you’re left with on the back of your eye lids, after a light bulb is switched off!

You may experience that this gets better the more you try it! My clients find that not only is this a more memorable way for them to remember ‘sums’ but it also starts to change their language in their beliefs about maths, “Oh, this is easier”, or “I feel a bit more confident about working things out”.

When I was younger, I loved reading books on magic tricks and memory. What fascinated me is how I could teach myself to memorise a deck of cards by associating visual images of the cards in my mind. Some memory champions tell a story in their minds, making connections between cards. This is a very auditory and visual way of memorising the cards.

There is plenty of brain science and evidence behind this. Tony Buzan has published many popular books showing how to consciously exercise the visual and auditory senses in memorising facts, shopping lists, numbers, and developing visual mind maps. Mind maps (being a predominant visual stimuli) were my bibles when it came to cramming in notes for exams! (I used one to create this article too).

This worked far better for me than just reciting or writing notes. During revision times in my tertiary education, a friend of mine used to walk around (K) and recite (A) notes whilst reading them. This was a very effective method for her to learn and memorise information, but not for me. (Notice that these learning style strategies are neither right nor wrong. They just work well for that individual and it is important to recognise this when observing how individuals are learning at their best).

Furthermore, in my coaching role, I see clients with learning difficulties (or learning differences, a term which is becoming more popular) who display strengths in either visual, auditory or kinaesthetic modalities. One client of mine developed a visual strategy in her mind for remembering all important dates in her calendar, through visually connecting dates and other visual imagery (time management was not her strong point when we first met, but this vastly improved after a few sessions of consciously engineering her own strengths using visual associations). The key here is that she suddenly became acutely aware that she could utilise a learning style that worked well for her. After realising this, her confidence around time management improved and she actually started turning up to meetings on time!

In principle we use all three modalities of V, A and K when learning, whilst not being conscious of them at the time. For those that drive a vehicle, think of the time you took your first few driving lessons and how you were able to coordinated your learning, without having the need to think about which senses you were using!

I believe it’s about making these senses (or modalities) part of conscious learning that can help shape a child’s mind, by being more self aware of them. It’s really quite easy to draw attention to them by isolating them into specific exercises. Here are a couple just for starters. These work well with two or more people.

Exercises 1 – Using V A K senses in language

• Think of a story or make one up. If in a group, organise a circle of people and have each say a few lines about the story with the next person picking up from where the last one left off. Each person describes their part of the story in a visual, auditory or kinaesthetic way. For example;

(person 1 – visual). It was a night where sparkly stars shone like diamonds in the dark blue sky.

(person 2 – auditory). Not a sound could be heard apart from the whisper of the quiet breeze.

(person 3 – kinaesthetic). A feeling of calm, touched the sole of the child who stood, holding on to the soft, warm hand of his mother…

Afterwards, check each persons experience of how they coped with the exercise and repeat if desired. Note, that any resulting laughter may well be part of the learning!

Exercise 2 – Utilising V, A and K senses as a ‘spot/hear/feel the difference’ game

• A person is observed by an observer, viewing them from a distance of a few feet. Then the observer turns their back for a few moments. The other person then changes just one or two things about their appearance (eg, turned up shirt collar, untied shoe lace, hair slightly tussled, etc). The observer then turns around and tries to spot the difference in the person from a few moments before.

• The game can be repeated in a similar manner for sound. This is best done with 3 or more people. Person A has their back to the others. The others approach A individually, clap and say their name. Repeat the process one or two more times to give A a chance to calibrate each sound associated to a name. Then each person approaches again and claps in the same way as they did before, but this time without saying their name. The idea is for person A to guess from each clap, who the person is. Swap around so that everyone has a turn.

• The game can be repeated using a kinaesthetic approach, by using the palm of a hand for example, to gently push on one shoulder of person A and saying their name at the same time. Here, it is what person A notices in any slight palm pressure differences, that is the important part.

These activities can be a useful way to introduce young people to the ‘awareness’ of their senses.

Finally, as educators (parents, guardians, teachers, etc) we can be more aware of a child’s learning preference within the context of a particular experience. What often gets misunderstood in some literature (about learning styles) is that there is an interpretation that a person is “visual”, “more kinaesthetic” or “definitely auditory”. This may be true in some contexts but they are not fixed states. We use our senses effectively in different contexts. If a child is struggling with one of way learning, the flexibility demonstrated by the educator in understanding this and then changing it, may support a young persons experience that there is not only one way to learn. Developing flexibility in ourselves to develop potential in a child, is very much our responsibility as elders.

Applying an understanding of different learning strengths through V, A and K learning styles can be very rewarding when a child suddenly says, “Oh, I get it now”, when we have shown flexibility in utilising a different learning style (or modality). As we well know, this can have the by-product of building confidence and self esteem in children, which can add into the mix of developing their potential. Happy learning!

By Brendan Dobrowolny

www.NLP4Kids.org/Brendan-Dobrowolny

This is a structurally sound article which reads in a very credible way. Your Plasticine example makes it simple to understand why this is a helpful area for parents and teachers to learn about.

I do feel that your “why” could be stronger. For example what would happen if a child’s preferred learning style is not acknowledged and missed? Your article focuses only on the benefits of recognising learning styles which may create a mismatch between the readers who are not yet doing this and are caught dealing with the effects. If you also included the effects of not recognising and responding to learning styles, you may capture the attention of people those who are yet to use learning styles in their teaching. For example, working with children who appear to lack concentration could be a s symptom of a learning preference not being addressed.

You’ve got the repetition of the word “learning” several times over which is great for your search terms.

Your referencing gives further credibility to what you are saying and I am particularly pleased that you have included a visual image to accompany an article of this title. Perhaps you could create an audio too and perhaps a book for the kinaesthetic people to hold!

Cracking article. Very informative and we’ll written

This overall ethos of positivity towards learning is a great foundation, backed up by practical methods. Great article.

An interesting read! I also particularly liked the the plasticine analogy.

I only came across the concept of learning styles as an adult and I see now that school could have been a very different experience if they had been a key ingredient of the teaching. I was reasonably successful, but I think that was down to determination to find a way to learn rather than because it was delivered in a way that worked for me.

There’s such an opportunity to use this knowledge to make the learning experience better for everyone. Who knows, maybe all subjects would be ‘easy’. Thanks for the food for thought, you’ve got my mind buzzing.

I loved this article! I am a mother of 3 teenage boys and Brendan, you have really made me think about how I can help and support them with their studies. You have left me wanting more! Thank you.

This is a well written and interesting article. I like the example of moulding plasticine – this shows that children can’t just be left to figure things out for themselves, teachers and parents also have a role to play in nurturing them. Although the concept of learning styles has been around for a long time, it is always useful to read others’ interpretatioons and ideas on the topic.

As a teacher, I am familiar with VAK and its applications for students’ learning but what is great about this article is how clearly you explain the concept, using supporting examples. It is so important that we utilise as many of our senses as possible when learning and memorising as this is what helps learning to stick. Younger children in particular also find VAK methods more fun & engaging and if a child is engaged in their learning then that is half the battle! I think it is good that you have pointed out the need for flexibility & for children not to be pigeon-holed into one particular learning style; their preferred learning style is not their only learning style.

As a Master Practitioner and a Coach of developing footballers (both children and adults) I found this article very interesting. One of the most important aspects of creating an effective learning environment is to ensure that it is bespoke for the learner or learners. This article is well written and highlights the key points in design of learning material to ensure the modalities are covered, and provides practical examples. I really enjoyed this article and will use this to help educate other coaches to deliver better sessions. Observing the ‘oh, I get it now’ moments, either verbally or through physiology is the most rewarding part and more and more coaches will experience this quickly using the key points in this article. Good work!

This is a well written and thought provoking article. It’s made me assess the different learning styles of my own children.